EDUCATION SYSTEM

Education in Nigeria

By WES Staff

This education profile describes recent trends in Nigerian education and student mobility, and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of Nigeria. This version is adapted from earlier versions by Jennifer Onyukwu, Nick Clark, and Caroline Ausukuya, and has been updated to reflect the most current available information

INTRODUCTION

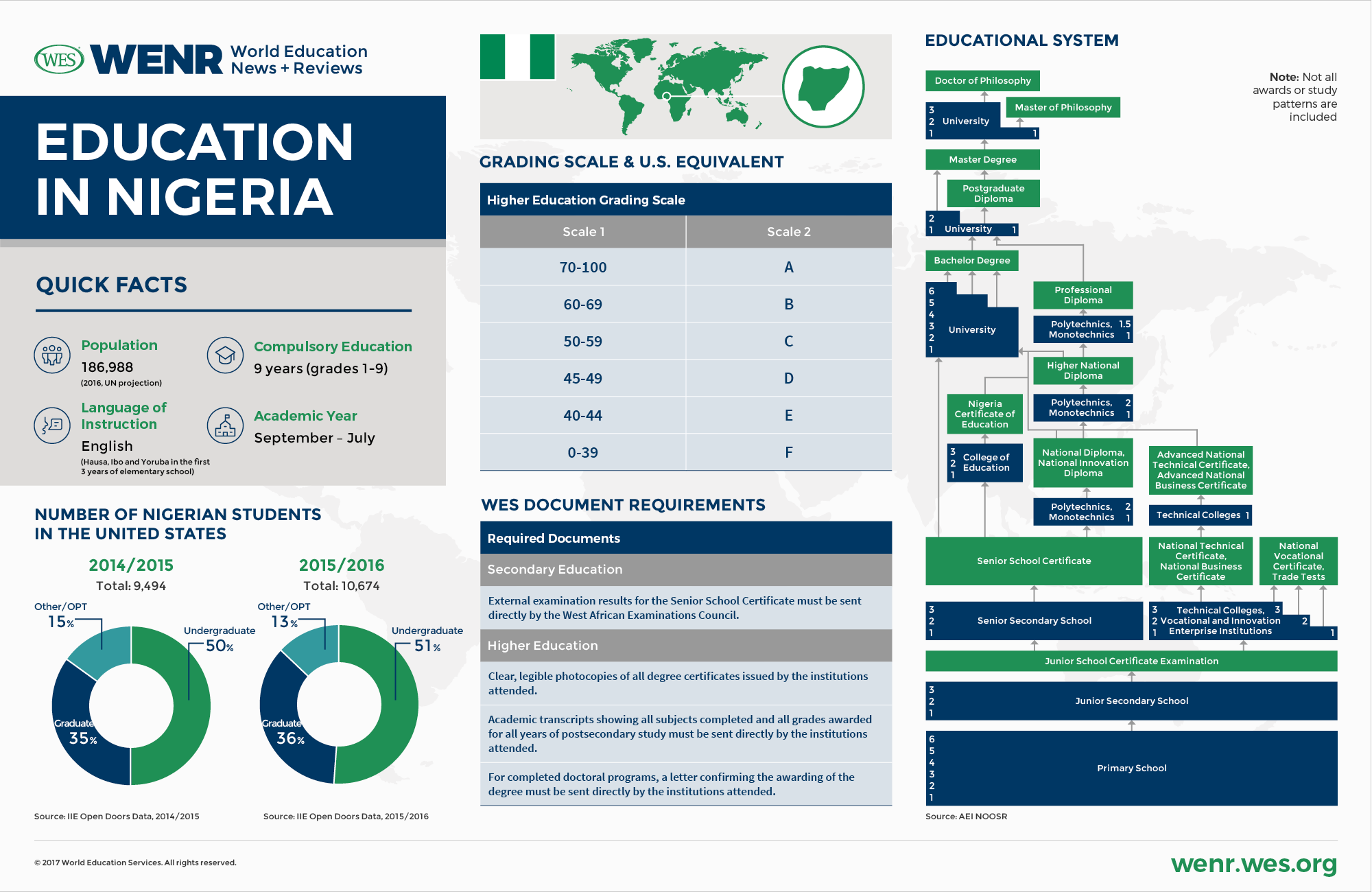

Almost one in four Sub-Saharan people reside in Nigeria, making it Africa’s most populous country. It’s also the seventh most populous country in the world, one with ongoing growth. From an estimated 42.5 million people at the time of independence in 1960, Nigeria’s population has more than quadrupled to 186,988 million people in 2016 (UN projection). The United Nations anticipates that Nigeria will become the third largest country in the world by 2050 with 399 million people.[1]

The country is of growing economic importance as well. In mid-2016, it overtook South Africa as the largest economy on the African continent, and was, until recently, viewed as having the potential to emerge as a major global economy. However, a substantial dependency on oil revenues has radically undercut this potential. Frankie Edozien, director of New York University’s Reporting Africa program, recently noted in The New York Times that crude oil “is responsible for more than 90 percent of [Nigeria’s] exports and 70 percent of its government revenues.” A sharp decline in crude oil prices from 2014 to early 2016 catapulted Nigeria into a recession that added to the country’s already long list of problems: the violent Boko Haram insurgency, endemic corruption, and challenges common to many Sub-Saharan countries: low life expectancy, inadequacies in public health systems, income inequalities, and high illiteracy rates.

Severe cuts in public spending following the recession have affected government services nationwide. In the education sector, the situation has exacerbated existing problems. Ongoing student protests and strikes have rocked Nigerian universities for years, and are a symptom of a severely underfunded higher education system. Austerity measures adopted by the Nigerian government in the wake of the current crisis further slashed education budgets. Students at many public universities in 2016 experienced tuition increases and a deterioration of basic infrastructure, including shortages in electricity and water supplies. The crisis also dried up scholarship funds for foreign study, placing constraints on international student flows from Nigeria.

Despite these constraints, the country will likely remain a dynamic growth market for international students. This is largely because of the overwhelming and unmet demand among college-age Nigerians. Nigeria’s higher education sector has been overburdened by strong population growth and a significant ‘youth bulge.’ (More than 60 percent of the country’s population is under the age of 24.) And rapid expansion of the nation’s higher education sector in recent decades has failed to deliver the resources or seats to accommodate demand: A substantial number of would-be college and university students are turned away from the system. About two thirds of applicants who sat for the country’s national entrance exam in 2015 could not find a spot at a Nigerian university.

INTERNATIONAL MOBILITY TRENDS: THE TOP AFRICAN SENDER OF STUDENTS

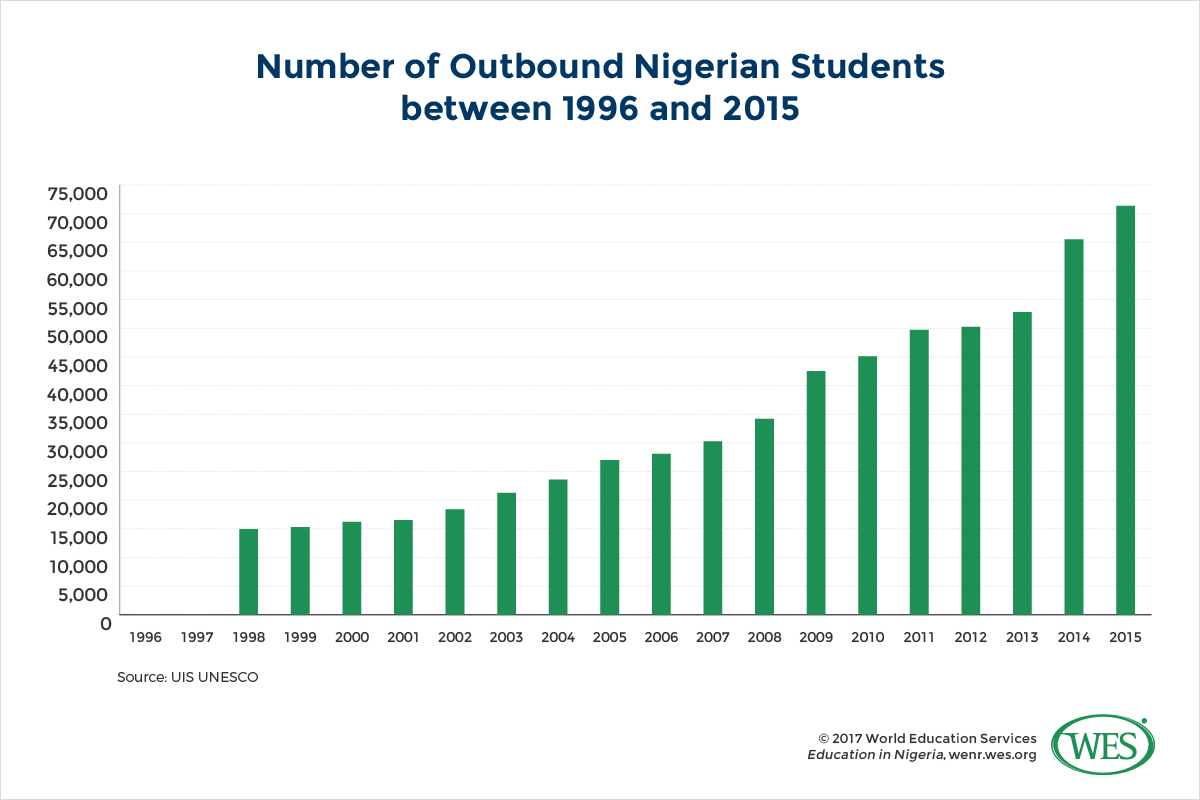

Nigeria is the number one country of origin for international students from Africa: It sends the most students overseas of any country on the African continent, and outbound mobility numbers are growing at a rapid pace. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent in the decade between 2005 and 2015 alone– from 26,997 to 71,351.[2]

In the short term, Nigeria’s oil price-induced fiscal crisis is likely to affect outbound student mobility. As many as 40 percent of Nigerian overseas students are said to rely on scholarships, many of which were backed by oil and gas revenues. The vast majority of these scholarships have been scaled back or scrapped altogether in the wake of the fiscal crisis. Further exacerbating the immediate prospects of Nigeria’s overseas students was a 2016 crash of the foreign exchange rate of Nigeria’s currency, the naira. The crash increased costs for international students, and reportedly left large numbers of Nigerian overseas students unable to make tuition payments.

But for all the short term upheaval, the push factors that underlie the outflow of students in Nigeria are fundamentally unchanged. These include:

- The failure of Nigeria’s education system to meet booming demand

- The often poor quality of its universities

- Rapid growth in the number of middle class families who can afford to send their children overseas

Given those drivers, it seems unlikely that the crisis will lead to a sharp and prolonged downturn of international student numbers.

Comments

Post a Comment